Learnings from Rains Retreat 2023

I was on a meditation retreat from 29th September until 6th November 2023 at Jhana Grove. It was especially fruitful during my personal 3-week silent retreat, from 2nd to 23rd October: during those times, there were days when I literally said nothing aloud to anyone. It’s one of the most enjoyable periods in my life.

Here are some of my learnings, which I’m sharing here. Hopefully these will be useful for some of you.

1. Contentment is the ultimate wealth; Sankhara is the ultimate suffering.

This first learning is taken from two sentences (from adjacent stanzas) in the Dhammapada: “Contentment is the ultimate Wealth” Dhp 204 and “Sankhara is the ultimate suffering” Dhp 203.

Before this retreat, I’d never really understood the idea of “contentment is the ultimate wealth”: it made no sense to me. If you’re contented, doesn’t that mean you won’t get more? So how can that be the ultimate wealth?

The best way to describe my new understanding is through the analogy of food (whatever is available in the five-sense world) and one’s stomach (mind).

- If your stomach is full, no matter how much is offered to you, you can’t stuff more into your stomach: it gets very uncomfortable. Similarly, when you’re content, your mind is “full” and you don’t want anything else. And as long as your mind is “full”, that is wealth.

- In contrast, imagine that no matter how much you eat, that you will never feel full, but you will always feel hungry. In that analogy, your mind is never “full”.

Another analogy is that of financial credit & debt ratios: if you have equity of $1 and you’ve loaned $6, it’s not different from a billionaire (net worth $1bil) taking out a $6billion loan. Contentment is removing all debt.

Shortly after my arrival at Jhana Grove, I asked my teacher Ajahn Brahm a question. How do I deal with the sense of ambition? I’ve constantly struggled between the horns of a dilemma: on one hand, I really appreciate the peace, calm and happiness from my Buddhist practice. On the other hand, I also have this strong sense of ambition, which manifests as a strong desire & inclination towards planning, doing, thinking, writing.

Ajahn told me to ask myself “and then what?”, and to play things out to their logical conclusion. “What if my ambition isn’t for myself, but actually for the Buddhist community?”, I asked. “That’s a bit of a bluff, “ he immediately replied. “I’m sure every Buddhist community would prefer having one more contented, happy, peaceful and enlightened person. And if there were more contented, happy, peaceful persons, then I would have fewer questions to answer, and can go back to my cave earlier after lunch…” I got the hint, and took my leave. :)

What happened over the next few weeks really drove home the point. There were a few meditation sessions which were largely spent with my mind generating will, thoughts, plans, comments, analyses. Then, as I practiced sense restraint (see next learning point), the thoughts, plans, comments, analyses died out naturally, to be replaced by moments of stillness, quiet, peace and calm. The peace and calm was so nice, in stark contrast to the previous stormy thoughts. It felt like I had travelled through the stormy part of a hurricane, only to enter its calm “eye”.

These experiences made me realize that contentment was about not-wanting, and that sankhara (which includes will, thoughts, plans, comments, analyses) was entirely driven by wanting and desire. And not-wanting was so much nicer! And then, suddenly one day, the two sentences from the Dhammapada made sense to me.

One day, after my restlessness had died out and my mind was again filled with calm, I suddenly had this terrifying question: how many lifetimes have I strived, thought, planned, commented, analyzed and basically did things, instead of being contented & still? That is still a thought which makes me shudder. The insight has started to turn me away from my thoughts. I’ve also started to place less weight on the value of my thoughts, opinions etc., as there are intrinsic defilements within thoughts and perceptions.

TLDR - contentment is *the way to Nibbana. And any kind of willing, doing, planning is suffering.*

2. The suttas aren’t the Dhamma: they point to the Dhamma, but are not the Dhamma itself.

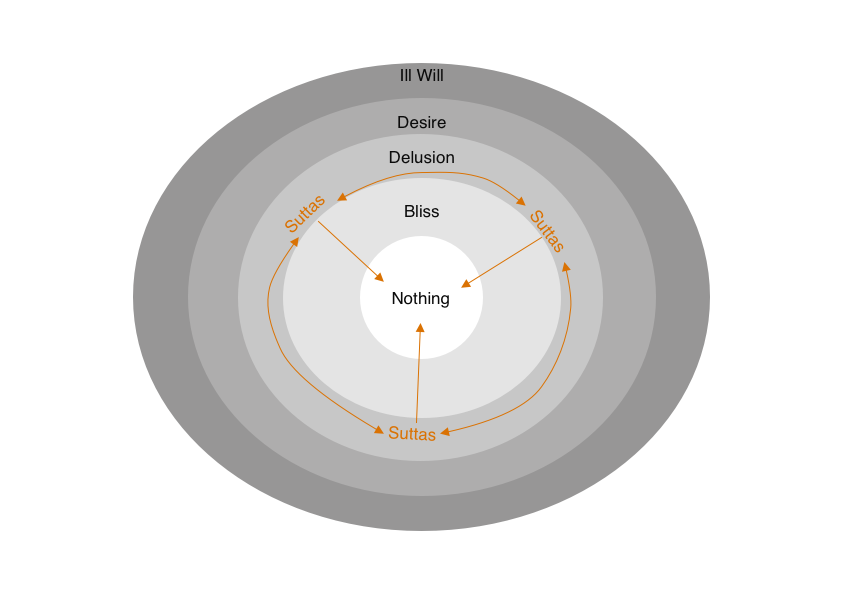

This point can be confusing, but basically, the suttas spell out the Dhamma, but they are NOT the Dhamma. Their relationship with the Dhamma is more like this:

Diagram taken from chat with Venerable Ananda

It’s in the same way that a restaurant menu (or picture) points to the actual food, but is NOT the actual food. Eating the menu wouldn’t really help you get full: similarly, just eating the suttas (and its concepts) will not get you full. Instead, it will just drive you around and around and around in a whirl of conceptual proliferation…

Diagram taken from chat with Venerable Ananda

It’s in the same way that a restaurant menu (or picture) points to the actual food, but is NOT the actual food. Eating the menu wouldn’t really help you get full: similarly, just eating the suttas (and its concepts) will not get you full. Instead, it will just drive you around and around and around in a whirl of conceptual proliferation…

So while the suttas are very important, one needs to have the wisdom to recognise that they are not the same thing as the Dhamma.

The Dhamma needs to be realized within each and everyone of us, and the only way to realize the Dhamma, is through practicing the whole Eightfold Path. Reading/listening/asking questions/debating about concepts like dependent origination are potentially a very big and dangerous distraction. Because you can literally go around in circles, rather than realizing the Dhamma (i.e. going inwards).

TLDR - Suttas are important, but they are the menu, not the food.

3. Don’t get caught up in the features and details of one’s perceptions, and don’t get dismayed!

A sutta which resonated with me this retreat was AN4.14 Restraint. This text has parallels in Gandhari and Chinese, so it is probably quite reliable.

The excerpt which resonated with me was this:

When a mendicant sees a sight with their eyes…When they hear a sound with their ears … When they smell an odor with their nose … When they taste a flavor with their tongue … When they feel a touch with their body … When they know an idea with their mind, they don’t get caught up in the features and details.

If the faculty of sight/sound/smell/taste/touch/mind were left unrestrained, bad unskillful qualities of covetousness and displeasure would become overwhelming. For this reason, they practice restraint, protecting the faculty of sight/sound/smell/taste/touch/mind, and achieving its restraint. they don’t get caught up in the features and details. If the faculty of sight/sound/smell/taste/touch/mind were left unrestrained, bad unskillful qualities of covetousness and displeasure would become overwhelming. For this reason, they practice restraint, protecting the faculty of sight/sound/smell/taste/touch/mind, and achieving its restraint. This is called the effort to restrain.

But why should we practice sense restraint? Another sutta SN46.6 To Kundaliya (with a Chinese parallel) explains this:

Buddha: “The benefit the Realized One lives for, Kuṇḍaliya, is the fruit of knowledge and freedom.”

Kundaliya: “But what things must be developed and cultivated in order to fulfill knowledge and freedom?”

Buddha: “The seven awakening factors.”

Kundaliya: “But what things must be developed and cultivated in order to fulfill the seven awakening factors?”

Buddha: “The four kinds of mindfulness meditation.”

Kundaliya: “But what things must be developed and cultivated in order to fulfill the four kinds of mindfulness meditation?”

Buddha: “The three kinds of good conduct.”

Kundaliya: “But what things must be developed and cultivated in order to fulfill the three kinds of good conduct?”

Buddha: “Sense restraint. And Kuṇḍaliya, how is sense restraint developed and cultivated so as to fulfill the three kinds of good conduct? A mendicant sees an agreeable sight with their eye. They don’t desire it or enjoy it, and they don’t give rise to greed. Their mind and body are steady internally, well settled and well freed. But if they see a disagreeable sight they’re not dismayed; their mind isn’t hardened, dejected, or full of ill will. Their mind and body are steady internally, well settled and well freed.”

So it is clear that sense restraint is necessary for liberation. And, when sense restraint is done right, it is actually pleasurable: the mind isn’t dismayed, hardened, dejected or full of ill will.

This is particularly important to note, because many people take a “hear no evil, see no evil, say no evil” approach to sense restraint, using a lot of willpower and force. They also often get dismayed: “why am I craving this so much??” and don’t realize that they have taken the wrong approach to sense restraint.

TLDR - Don’t grasp at the features and details of whatever you perceive. Just acknowledge and let go.

4. The fuel for restlessness is focusing on one’s restlessness. Focusing on one’s settled mind starves future restlessness (SN46.51)

Another text which resonated with me was SN46.51, which describes (in some detail) the causes for the Five Hindrances & Seven Enlightenment Factors. It’s a relatively longer text.

The particular excerpt which resonated was this excerpt, explaining that the more you focus on restlessness, the more that fuels restlessness:

There is the unsettled mind. Frequent irrational application of mind to that fuels the arising of restlessness and remorse, or, when they have arisen, makes them increase and grow.

The opposite (which starves restlessness) is to focus frequently on the settled mind:

There is the settled mind. Frequent rational application of mind to that starves the arising of restlessness and remorse, or, when they have arisen, starves their increase and growth.

There is tranquility of the body and of the mind. Frequent rational application of mind to that fuels the arising of the awakening factor of tranquility, or, when it has arisen, fully develops it.

Taken in totality, this means that after meditation, it is less important to focus on one’s restlessness, and much more productive to focus on the moments of peace (no matter how short!) one experienced in the meditation.

TLDR - Water your flowers, not your weeds.

5. Listen and adjust, all the time.

This was a personal learning. At the start of my retreat, I decided that, instead of forcing myself and using will, I would instead just play by ear, and just continuously listen to my body and mind, and adjust to its needs (not wants!), all the time. It was a form of applying mindfulness and kindness.

Quite often, I would sit and my body would end up feeling slightly tense (especially around my lower spine, back and neck). In the past I would “tough it out” by telling myself to ignore the discomfort, to “let it go”… and end up being in even more discomfort!

This retreat, I would note the discomfort, and instead of toughing it out, I would then gently and subtly adjust my posture a little bit. And every day, I was listening and watching my own mind and body, seeing what both needed.

There was one day when I struggled with meditation: I woke up late, and really struggled with sleepiness the whole day. In the evening, as I wrote my diary, I realized I was extremely tired: so I went to bed at around 6pm, and just slept. The next day, everything felt normal. In retrospect, I wonder if my body was not feeling well that day, and I had listened to my body’s needs: as a result, I didn’t fall sick the whole five weeks, even though I was in close contact with a few Covid patients in the last week.

TLDR - be kind to your mind and body, at every moment

6. Let go of personal preferences.

Another personal learning, linked to the understanding that “sankhara is the ultimate suffering”.

If sankhara is the ultimate suffering, then I shouldn’t be following them so tightly. So a resolution I kept (and still kinda follow nowadays) was to let go of my personal preferences, and to go with the preferences of the other people around me (as far as possible).

This is easier in a retreat than in daily life, tbh: in daily life, I still ultimately hold the responsibility for my own welfare, so I am forced to ask myself what I really want.

But this has made it a lot easier to just go with the wishes and preferences of others.

TLDR - let go of your self and its preferences, by going with others’ wishes and preferences

The remaining three learnings came from a very dramatic bushfire which threatened the retreat centre and monastery on the day that the retreat ended, just the day before the monastery’s Kathina . It was a very interesting experience, which I don’t think I will forget! At one point, a fireman told everyone “Guys, Kathina is NOT HAPPENING. There is a FIVE PERCENT CHANCE that Kathina will happen!”…and I stayed (with my wife, and three other new friends) to see the five percent. :)

7. Good behaviours require no explanation; bad behaviours have Reason as a bodyguard

When the bushfire incident happened, I observed a large range of behaviours from my fellow retreatants.

What was really interesting was that, when people did something good, there were usually little or no explanations given (or expected): people just gave a simple description and did it.

For example, one of my fellow retreatants came up to ask me if we should prepare food for the volunteer firemen (there were two of them, Matt and Ron, in a firetruck at the carpark). When I said that I had already offered them food but they said no, he replied, “They might not feel it’s right to say yes, but I don’t think they will say no if we prepare food for them; let me organize that” and he left to organize the sandwich-making party. Similarly, nobody said “please let me do more good: I need to make more good kamma to survive the bushfire”: people just helped out, which was wonderful and super inspiring to see!

In contrast, when more self-centered requests were aired, invariably these requests were accompanied with a lot of reasoning and logic, along the lines of “I need _ , because of __, __ and ___.”

It reminded me of an episode from my childhood. My parents sent me to a martial arts class every Sunday to “toughen me up” as a kid. It was a very harsh environment, and I always dreaded going to the class. I became an expert at coming up with all kinds of lies (I didn’t keep the five precepts as a kid, for sure!), because of this overwhelming sense of dread. And in my mind, I thought that it was better if I could come up with more reasons why I shouldn’t attend the lesson: I have a fever, an important test that week, AND my asthma was also acting up.

It’s a tell: if your mind is generating multiple reasons why you should or shouldn’t do something, that probably means your motivations are less than noble.

It also reminded me of this classic quote from David Hume:

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

TLDR - the more reasons you’re generating to justify your actions, the more you should be suspicious of your real motivations.

8. Positive emotions can substitute and displace negative emotions

The people who showed gratitude to me in person were often the ones who also showed no fear. The reverse was true: the ones who were overcome with fear were often the ones who expressed zero gratitude in person.

To me, this points to a possible solution to fear (& other negative emotions) that the Buddha mentioned in MN 20. If you have a negative emotion, substitute it with a positive emotion by choosing a perception that generates that positive emotion.

TLDR - if you’re in the middle of a negative emotion, choose another perception which generates a positive emotion (like gratitude), to displace the negative emotion.

9. What is your real refuge?

The last learning from the bushfire was a question of refuge. Taking refuge means that you rely on something as a place of refuge, a source of safety.

It seemed to me that many people were taking refuge in the five sense world, and not really in the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha. Because they were constantly holding on to some hope that they can control the world of the five senses to their benefit. Their fear-driven desire (or desire-driven fear: same thing) then drives them to rationalise and proliferate. They can’t let go.

You know what is actually scarier than a bushfire? It’s the fires of greed, hatred and delusion. Because these three fires will cause you to repeatedly suffer and suffer. See the famous fire sermon. And what is the fuel for these three fires? Wanting of the five sense world.

It also seemed to me that many people might have a mistaken understanding of Ajahn Brahm’s teachings: Ajahn’s teachings are not just fun, bad jokes and games. Ajahn is actually teaching all of us how to live well, and thus actually also how to die well. Thus, the potential life death situation we faced in the bushfire was actually almost like a final exam for our own practice.

If one’s mind was steady, and one was ready to let go of one’s life even, and focus on letting go, kindness and caring for others, then one probably really understood and trusted in the Buddha Dhamma Sangha.

I would strongly encourage most people to take their Dhamma practice more seriously. Always be mindful and kind, by body speech and mind. Practice like you will die in a bushfire. Or, as the Buddha said, like their hair is on fire. Seriously. people might know intellectually that they can die at any time, but emotionally they might actually still be in denial.

Because absolutely nothing in the five sense world is within our control. The sooner we accept it, the easier and smoother our practice and our lives.

Coincidentally, after my retreat, I read a brilliant Dhamma talk by Ayya Vayama on exactly this topic, about what is our real refuge. Unfortunately I can’t seem to find the pdf of the talk: if you can, I highly recommend reading it.

TLDR - what is your real refuge: the material world or the Teachings?

10. How to be a “monk at home” without the Vinaya

In Jully, I visited Luang Por Ganha in July, and he had given (me) the advice of “be a monk at home, then be a monk in the monastery”. By that, he meant to practice towards being a streamwinner (and above) while at home.

During my silent retreat, the more I thought about it, the more it seemed to me to be an insurmountable puzzle. Because the monks have the Vinaya, which is a set of rules, but also is a kind of training programme which the Buddha had put in place for the monks, to train towards liberation. As a layperson, how could I then “be a monk at home”, when I don’t have the training guidance of the Vinaya? How could I be sure that I wasn’t simply being led by the nose by my defilements?

So after I finished my silent retreat, I went to look for Ajahn Brahm one day, and asked him exactly this question.

Ajahn gave a brilliant answer.

- live simply. renounce, simplify one’s life along the lines of the gradual training.

- Meditate a lot.

- Do acts of service, but don’t let others know you did them. Don’t do things which build up your sense of self.

- Beyond keeping precepts, practice sense restraint.

TLDR - simplify your life along the lines of the gradual training; meditate a lot; serve without credit; sense restraint

Tags #dhamma-learnings #rains-retreat #dhamma

Written on: 26-Nov-23 at 10:53

Finished on: 4 Dec 23 at 16:53