Art, Design and Innovation

(Reposting this from an older blog post that I wrote when I was at CIID)

There remains one a priori fallacy, or natural prejudice, the most deeply rooted perhaps of all which we have enumerated… that is, that the conditions of a phenomena must, or at least probably will, resemble the phenomenon itself.

John Stuart Mill, “A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive”

Recently during the spring break, I re-read the book “Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned” by Kenneth O Stanley and Joel Lehman. The book’s ideas are especially applicable for domains which I think broadly of as “search” i.e. one is exploring a “search space”, much like a treasure hunter. This contrasts with “execution” domains, where there is often much greater clarity about the domain, and the focus is just on doing. The recent book “Trillion Dollar Coach” talks about the innovation vs execution spectrum; the ideas of “Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned”are largely applicable to search & innovation.

I remain amazed that there aren’t more blogs, essays or articles summarizing this book, as I think the book’s ideas have HUGE implications for art, innovation, design, and society at large. That is why I will attempt to summarize, and spell out the implications of this book’s ideas here today.

To understand the background, you first have to understand the experiment that sparked the insights.

Background: Picbreeder and Open-Search

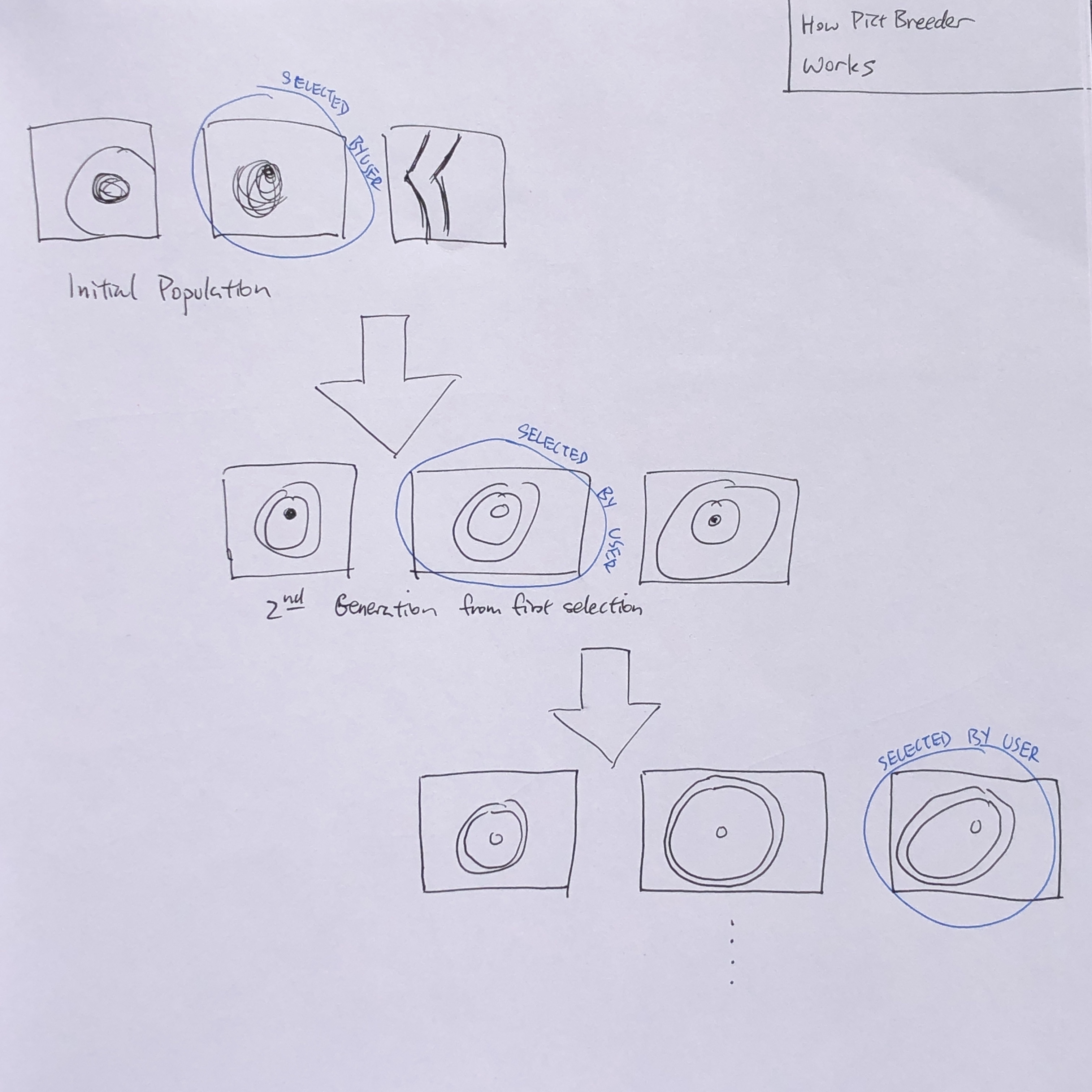

My pen-sketch on how Picbreeder works

Picbreeder is an online website that allows any user of the website to “breed” pictures. From an initial population of blobs and lines, a user can select a desired picture (see blue circle above); the website’s algorithm then generates a new set of pictures, using the “genome” of the selected picture.

This goes on, ad infinitum, until you basically end up with a genealogy of images, with different branches of family trees (kinda like my extended family, which has some “dotty” and weird branches…).

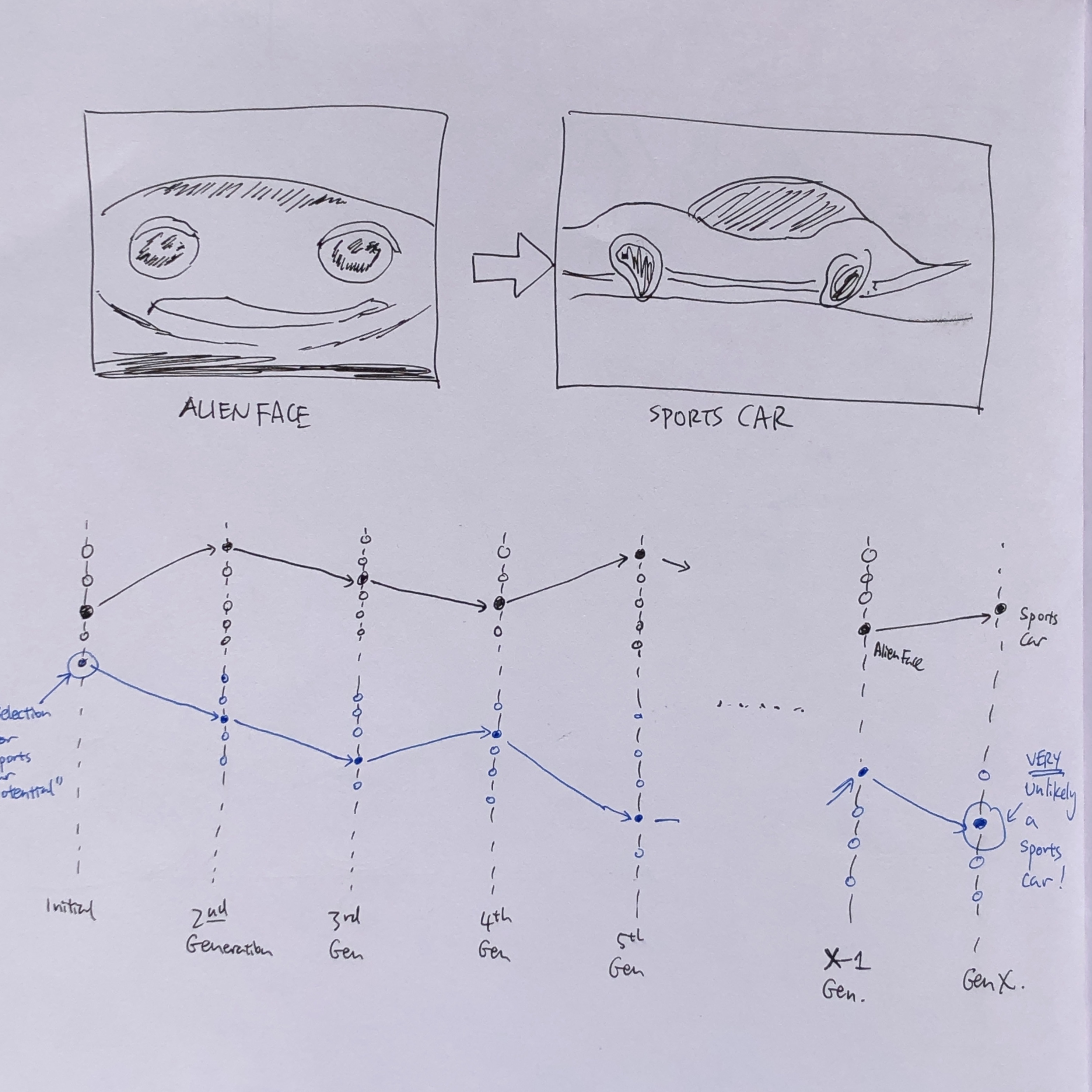

Stanley explained that he got his key insight when he suddenly ended up with a sports-car picture. Prior to that, he had selected an alien face. How, he thought, did an Alien Face lead to a Sports Car? It was by accident! Most importantly, he realised that if he or anybody earlier had selected earlier images for a Sports Car, he would NOT have ended up with a Sports Car. Because the Alien Face is a critical stepping stone to the Sports Car, but looks nothing like it (a la John Stuart Mill’s quote above).

How to get a sports car vs how NOT to get a sports car

So if you see the bottom half of the picture above, if the selection process had started filtering for sports car, it would have filtered out the useful genes that ended up being the Sports Car’s “parts” (e.g. the wheels were derived from the Alien eyes). If you had sought out a Sports Car at the start, you would likely NOT end up with a Sports Car, because you would have missed the stepping stone (i.e. Alien Face) to the Sports Car. In other words, setting ambitious “objectives” is actually self-defeating, as the objective leads one away from objective. Objectives don’t work, unless you’re just one-step away (e.g. Alien Face to Sports Car). Stanley is quick to articulate that this concept is only applicable to ambitious objectives, i.e. objectives that are very far from where we are now.

The two catches that complicates the search for these stepping stones are:

- It is impossible to know in advance exactly how many stepping stones away you are from the objective. Stanley made the comment that the Apollo moonshot happened to be one-step away from the technological boundary of that era, but they didn’t know it when they started. (It’s quite shocking to my mind to consider what the parallel universe would have been like, if we never succeeded in putting a person on the moon.)

- It is also impossible to know in advance what stepping stones lead to the objective. I think the example of convergent evolution illustrates how different stepping stones lead to the same objective: fish, dolphins and ichythosaurs look superficially alike. However, the stepping stones to each streamlined shape from each type of animal were quite different, and this shows from the unique differences of each physiology e.g. fish have gills, dolphins have blowholes etc.

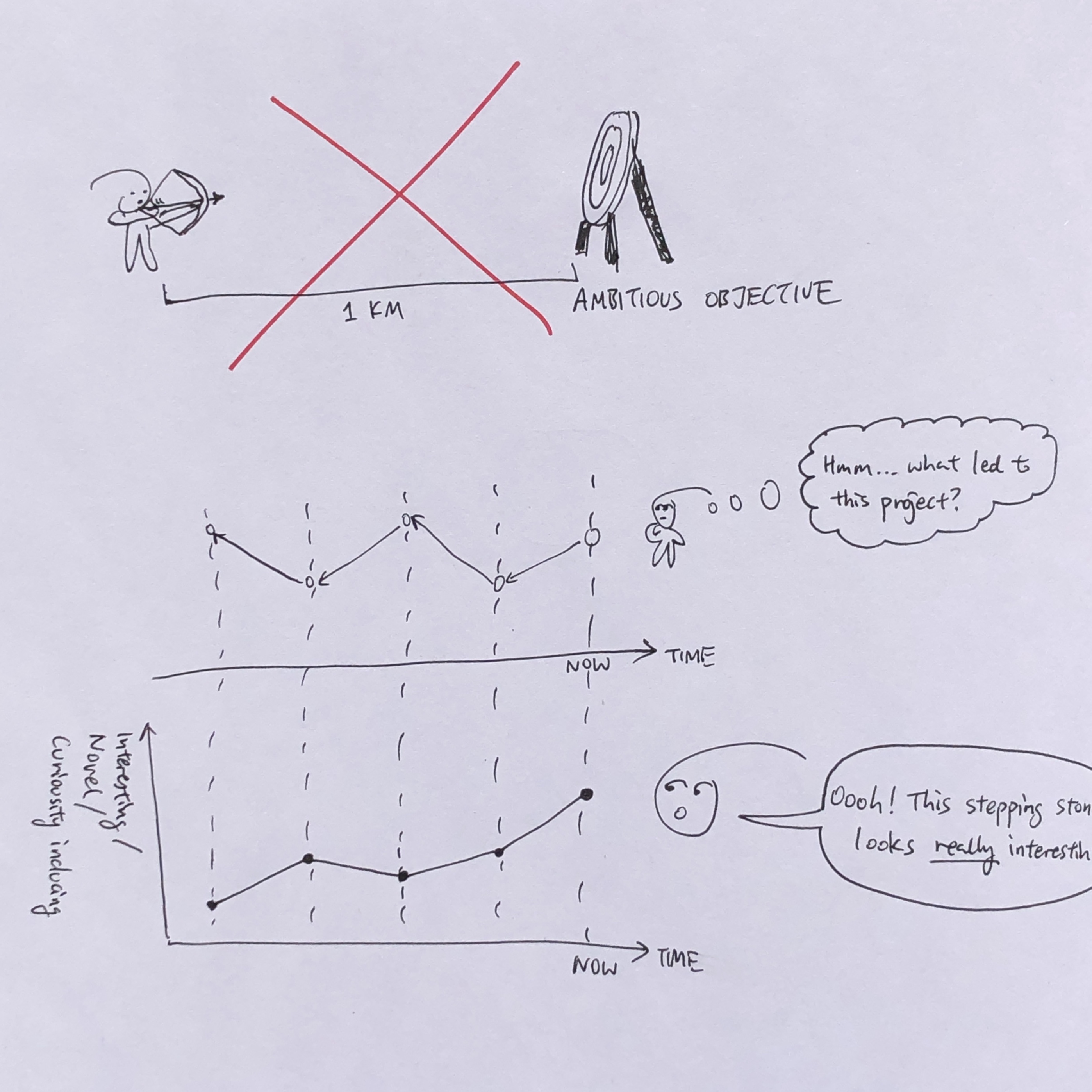

Recommendation: evaluating stepping stones by comparing backwards

Instead of setting ambitious objectives at the start of our journey, Stanley advocates that we should instead constantly look backwards, and compare where we are with where we were. The past projects/prototypes/ideas provide a reliable ruler for whether our current step is relatively interesting or novel.

Don’t set ambitious objectives. Instead, look at the previous stepping stones, and gauge whether this current stone is interesting or novel.

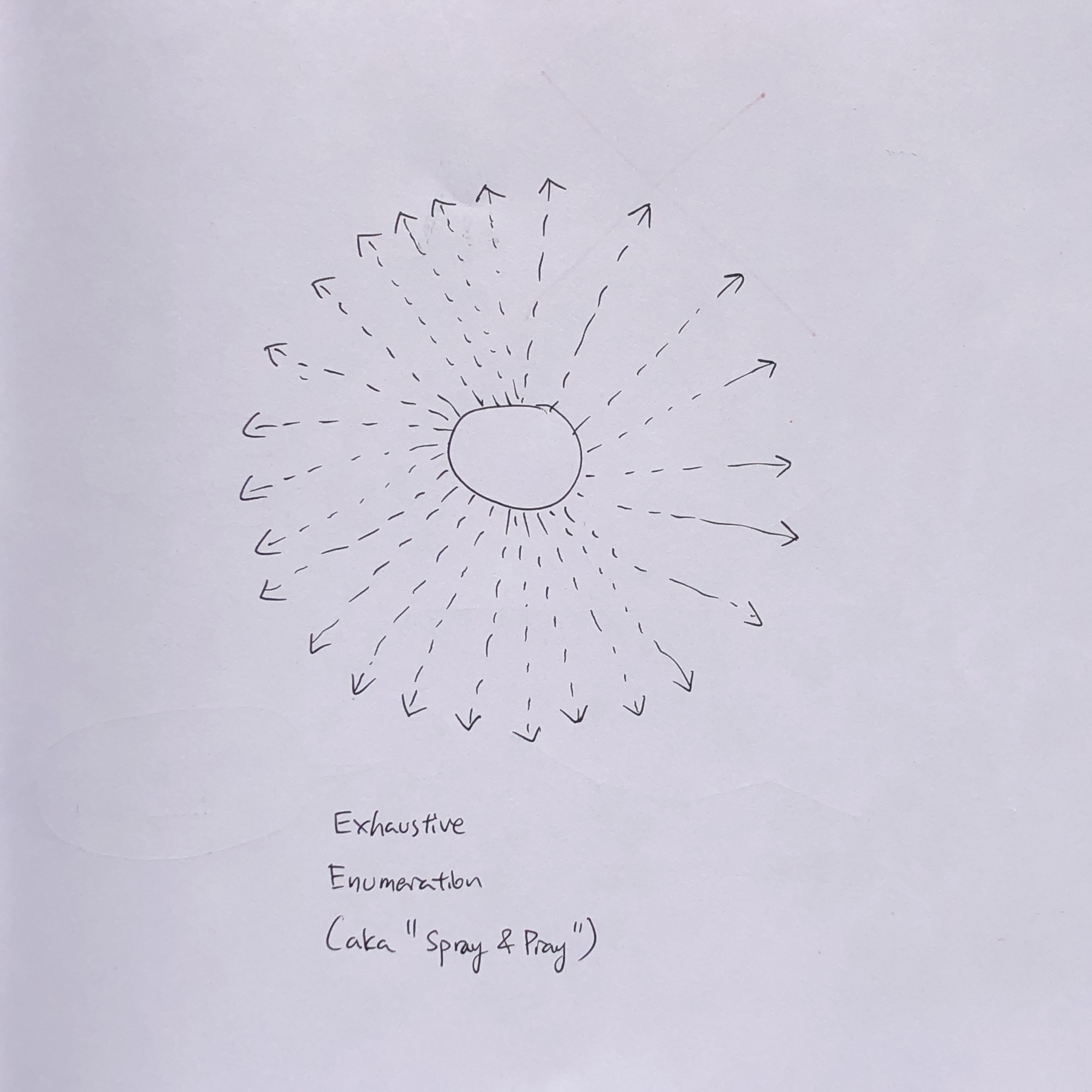

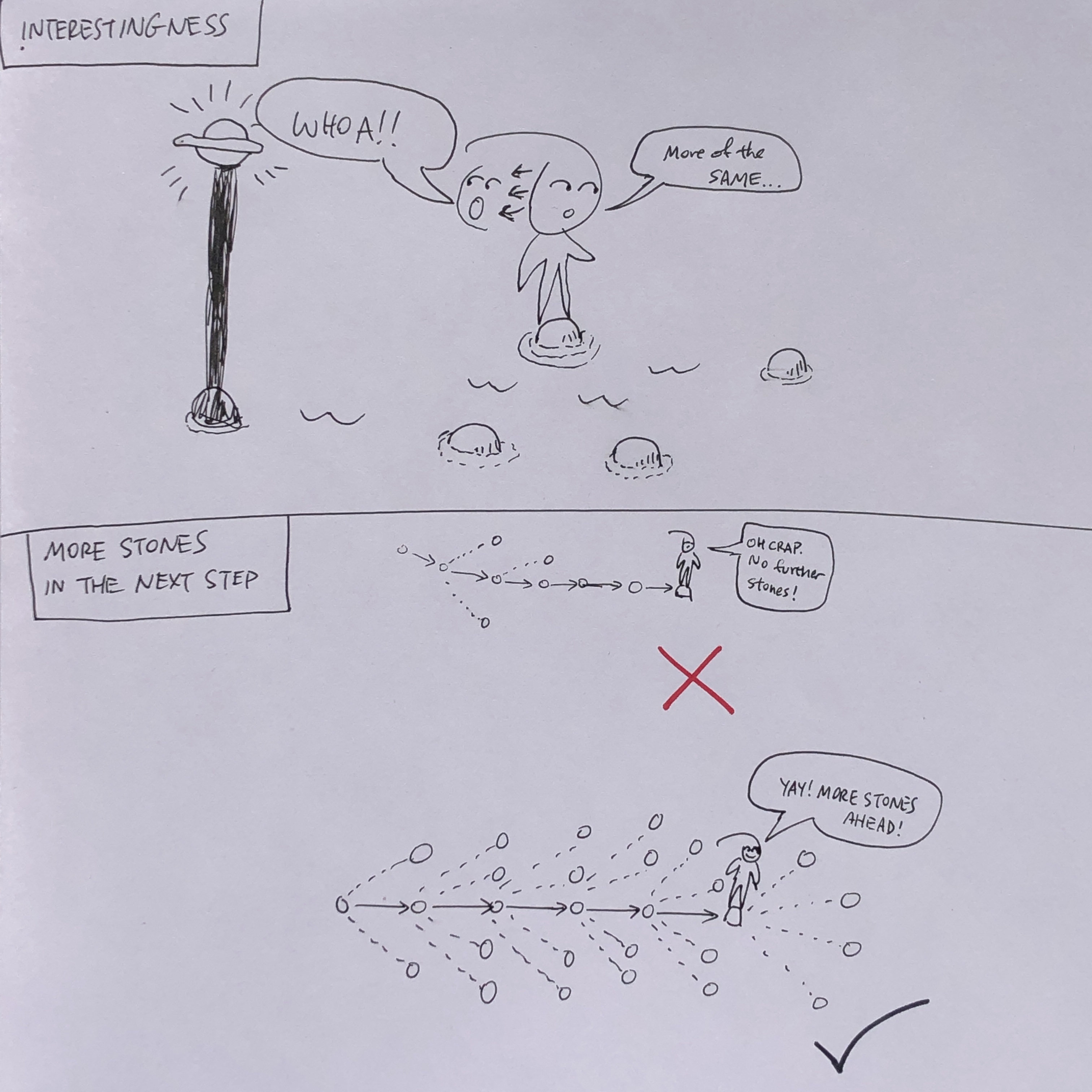

This is NOT exhaustive enumeration i.e. spray-and-pray, which graphically in my mind is a bit like this:

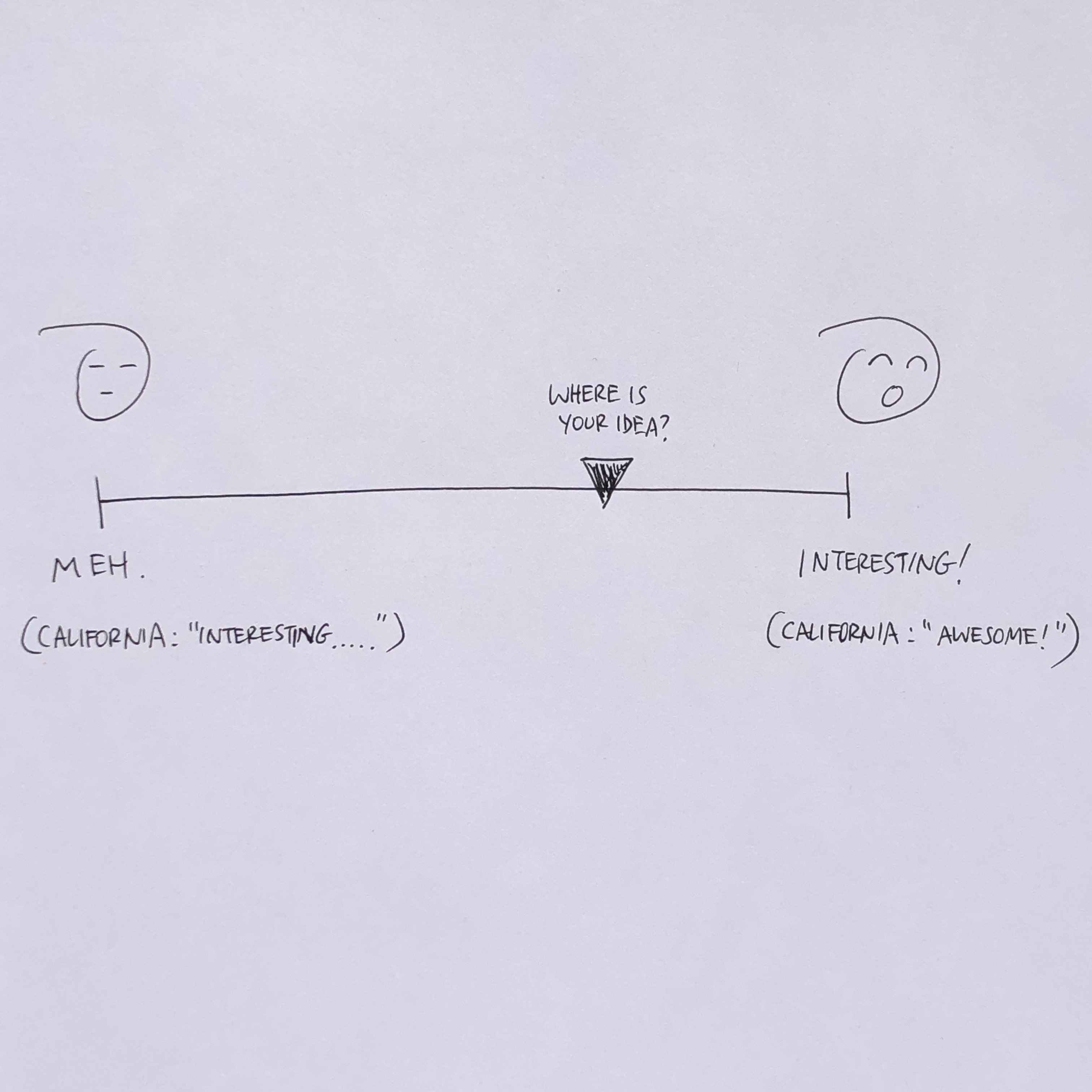

Rather, it is about using interestingness and novelty as a way to order your ideas, i.e. to put them in some sort of scale or order.

So rather than setting ambitious objectives, Stanley advocates using two criteria to evaluate stepping stones:

- Interestingness

- Whether the stepping stone leads to dead-ends or more stepping stones. (Note: this reminded me of Matt Nish-Lapidus’ comment in our Introduction to IxD that a good “how might we” statement is one that allows you to continue the work i.e. generating ideas, and eventually prototypes, etc.)

Interestingness, & Whether a Stepping Stone yields more Stepping Stones ahead

With these criteria, Stanley then advocates a treasure hunter approach i.e. for creatives and innovators to constantly collect and find new “stepping stones”.

I should add that the book is littered with TONS of examples taken from scientific discoveries, business research, innovation, art etc., of how innovation has evolved, and how these stepping-stone collection ideas otherwise work.

Implications

“A false visionary might try to look past the horizon, but a true innovator looks nearby for the next stepping stone. The successful inventor asks where we can get from here rather than how we can get there.”

Kenneth O Stanley, Joel Lehman, “Why Greatness Cannot be Planned”

I think this has a few major implications, especially in the fields of art, design and corporate innovation.

- Corporate innovation KPIs, especially those of blue-sky innovation and “moonshots”, are probably all wrong.

From what I know of typical corporate KPIs for innovation and R&D, the ambitious ones are probably shooting themselves in the foot. I’ll be curious to hear if there are any innovation KPIs that instead track the “interestingness” and whether the stepping stones lead to more stepping stones. - It might be more productive if the responsibility of answering the question of “Why this art/work/project” lies NOT with the artist/innovator/etc who came up with the art/work/project, but with the audience, especially any treasure hunter in the audience.

My classmate Silvia Sgualdini shared a great lecture with us, talking about the art world (she used to run the Liverpool Biennale). Part of her inspiration was from listening to a few artists who presented to us, and asking the question “why did they do this?”In my mind, this is a bit like asking Picbreeder “why did someone select this blob?”: it is a fruitless inquiry. Instead, it might be more useful if we ask ourselves “why this art/work/project could be interesting for me”, as that allows us to generate possible “cross pollination” of ideas in our minds. - The main job of design might be to collect and cross-pollinate stepping stones, and especially to test if the stepping stones are one-step away from something interesting.

This week, we had our “Design Look and Feel” course, with a focus on developing our aesthetic sensibility. We have had many discussions this week about what is aesthetic and what isn’t; there isn’t a clear universal definition of what is “aesthetic”, regardless of what Plato and other philosophers think.In fact, a few classmates were quite uncomfortable with the very broad-open-ended assignment we had this week, which yielded a few comments that it felt like “art class” rather than a design class. But my main takeaway from this book is that, that’s perfectly ok. It is perfectly ok for us to go with our gut instinct, and for us to just explore what we feel like. Because we have no idea what sort of stepping stones it might lead, and which other interesting directions it might lead. A classmate pointed out that she understands that this sort of “art” might be useful within the ideation phase of design. And that is probably true! In which case, then perhaps the main job of design is to collect, cross pollinate and test stepping stones, to see if they are one-step away from something interesting. - Futures and design futures might be all wrong.

This is going to be controversial, especially with the futurist community that I know personally… but with the ideas of the book, it seems to me that trying to look far into the future, creating “design futures” scenarios of 20-30 years out, etc. is exactly what we should NOT do. This is especially the idea of a “cone of plausibility” is extremely biased by your current worldview and state of technology.So perhaps instead of long-term futures and scenarios, perhaps design futures should focus instead on where we are, where we were, and what could be possible in the next 3-5 years. Just saying.