Career Advice (Updated 6 Aug 21)

My LinkedIn profile gets a lot of random queries from people who connect to me for career advice.

Initially, I was quite annoyed, & I tried to turn off the setting that randomly paired with people whom I don’t know. But I realised that, maybe I could be of service to people in a small but substantial way.

So, I’ve been giving the same advice to various people over the past few years over LinkedIn. This advice is necessarily general, but I think it is useful to consider how it might apply to your individual circumstance.

[Sidenote: I only accept LinkedIn invites from people that I’ve actually met and interacted with. I.e. we’ve met in person, and/or we have had a substantial exchange, like a chat, email exchanges, voice call, etc. This is to keep my LinkedIn network real, and not full of rubbish contacts whom I don’t know.]

————-

Best career advice ever

Best career advice ever

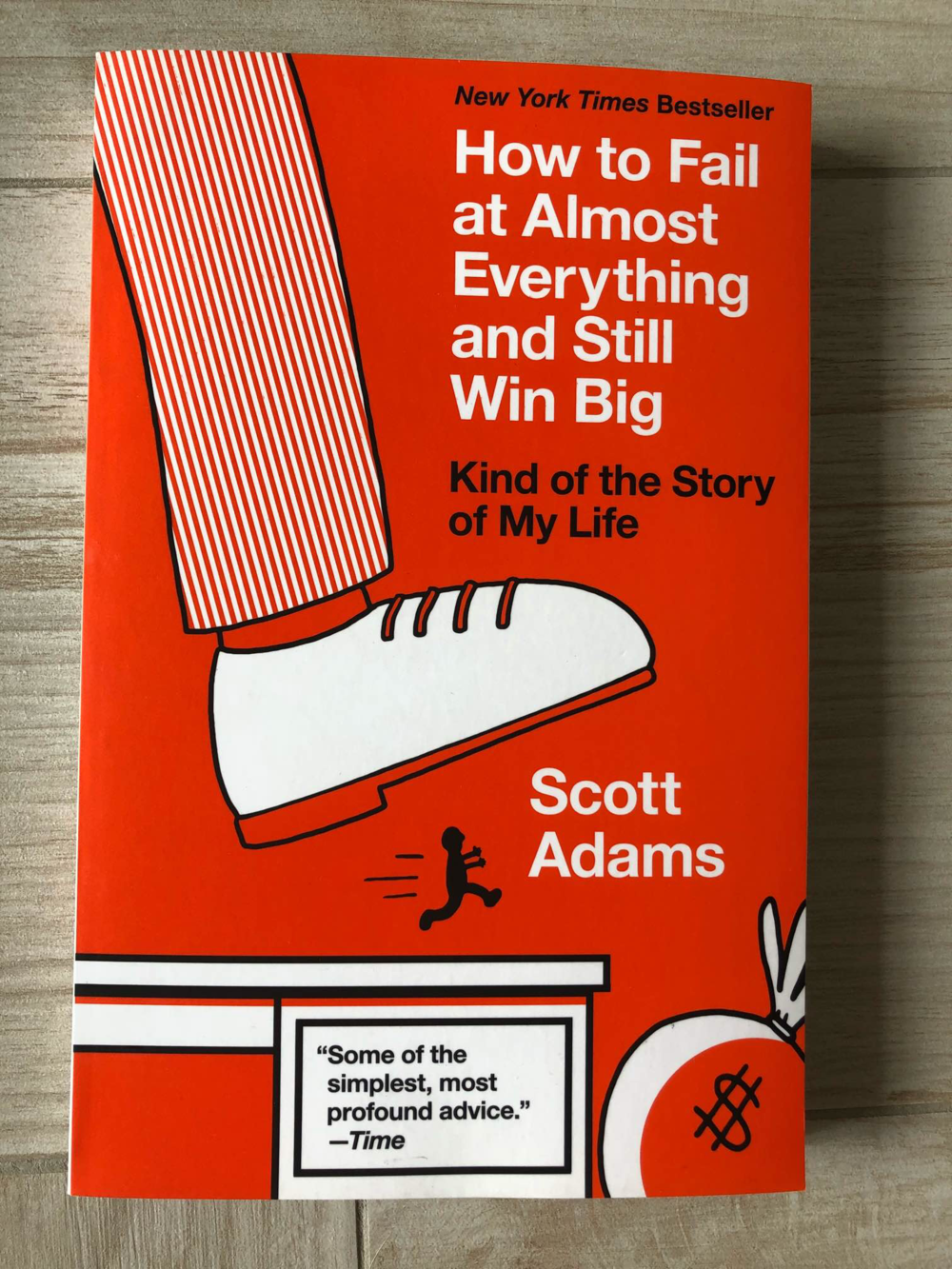

1. Read the best book on career advice I know, which is Dilbert-creator Scott Adams’ “How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big”. I totally wish that I had read this book earlier in my career. So I totally recommend it, for everyone who’s thinking and concerned about your career.

2. Think about your career in two time-frames concurrently. The first is that of the immediate: you could die anytime. The second is that of the long-term: you could very well live till you’re 100.

So I think your career choice has to be made in terms of the two time-frames.

On one hand, life is too short and unpredictable for you to be shoveling shit, day-in, day-out.

On the other hand, you also need to account for the possibility that you might be working for decades. So, would you really want to be shoveling shit for decades on end, using your life for that? When you die, do you really want to look back at the time you’ve spent and which you cannot get back, and think “damn…. that sucked”?

The implication of both time frames is that, you need to find something that you’re comfortable doing with the day-to-day (imagine if your dying moment was a view of an Excel spreadsheet) but also with sufficient longevity that you could do it for a while.

The flip side is that, if you have landed on something which you can see yourself doing for decades, AND you love doing the day-to-day, you’ve probably landed on something sweet. So this advice is both a framework to think about your career, as well as a litmus test of sorts if you’ve found career-fit.

3. Read Paul Graham’s essay on “How to Do What You Love”](http://paulgraham.com/love.html). It’s a long essay, but has a lot of meat in it about thinking about jobs vs passion. While I broadly agree with Cal Newport that passion tends to be overrated, at the same time, if you don’t discover your passion for something, it is very hard to be so good that they can’t ignore you. And you need discipline to experiment and discover what exactly you want to do, which you can be good at. My favourite passages below:

All parents tend to be more conservative for their kids than they would for themselves, simply because, as parents, they share risks more than rewards. If your eight year old son decides to climb a tall tree, or your teenage daughter decides to date the local bad boy, you won’t get a share in the excitement, but if your son falls, or your daughter gets pregnant, you’ll have to deal with the consequences.

…

Don’t decide too soon. Kids who know early what they want to do seem impressive, as if they got the answer to some math question before the other kids. They have an answer, certainly, but odds are it’s wrong.

A friend of mine who is a quite successful doctor complains constantly about her job. When people applying to medical school ask her for advice, she wants to shake them and yell “Don’t do it!” (But she never does.) How did she get into this fix? In high school she already wanted to be a doctor. And she is so ambitious and determined that she overcame every obstacle along the way—including, unfortunately, not liking it. Now she has a life chosen for her by a high-school kid.

When you’re young, you’re given the impression that you’ll get enough information to make each choice before you need to make it. But this is certainly not so with work. When you’re deciding what to do, you have to operate on ridiculously incomplete information. Even in college you get little idea what various types of work are like. At best you may have a couple internships, but not all jobs offer internships, and those that do don’t teach you much more about the work than being a batboy teaches you about playing baseball.

In the design of lives, as in the design of most other things, you get better results if you use flexible media. So unless you’re fairly sure what you want to do, your best bet may be to choose a type of work that could turn into either an organic or two-job career. That was probably part of the reason I chose computers. You can be a professor, or make a lot of money, or morph it into any number of other kinds of work.

It’s also wise, early on, to seek jobs that let you do many different things, so you can learn faster what various kinds of work are like. Conversely, the extreme version of the two-job route is dangerous because it teaches you so little about what you like. If you work hard at being a bond trader for ten years, thinking that you’ll quit and write novels when you have enough money, what happens when you quit and then discover that you don’t actually like writing novels?

Paul Graham, “How to Do What You Love”

4. Read Jessica Livingston’s great essay “Grow the Puzzle Around You“. Long essay of a completely different style from Paul Graham’s (who is her husband), but I totally loved it. My favourite passage below:

I was almost uncannily well suited for the kind of work it took to make YC successful. But the things that made me well-suited for it were so far from the qualities most people associate with startup founders. I’ll list them so you can see for yourself. I was the social radar, a good event planner, maternal, empathetic, a straight shooter, and not driven by money or fame. Think how far that is from the profile of the typical startup founder you read about in the press. Maternal? Since when was that an important quality in a startup founder? Let alone the founder of an investment firm. And yet it was critical to making YC what it is….

I recommend you try asking yourself what’s distinctive about you. What unique combination of abilities and interests do you have? And don’t edit your answers, because as my example shows, the most unlikely ingredients could be the key to the recipe. In fact, it may even be that the strangest combinations of qualities are the most valuable. I had a weird combination of qualities, but they matched YC because it was such a weird company.

5. Ultimately, it’s about YOUR happiness. Not mine, not the internet’s, not your parents’. If you’re perfectly happy knitting sweaters and making a just-enough living that covers your needs, power to you! If you’re perfectly happy striving to be a master-of-the-universe dealmaker, power to you too! The key thing is, only you yourself should judge if your career is good or bad. If people look down on you or think you’re stupid or whatever, well, fuck’em. It’s your life.

6. Act on the advice: experiment by trying and doing. It’s not enough to just read about jobs or talk to people about their work: they are not you. And you, are also not you: what works for you when you’re 20 might not work for you when you’re 40, 50 or 60, and vice versa. You can only really know when you’ve tried and done.

Personally, I was super surprised by how I loved learning to code in the Interaction Design Programme; the other thing was also how much I loved generating wireframes and app flows on Sketch. I had zero idea at the start of 2019 that I would discover these new loves.

——

As always, caveat emptor: please use discretion and common sense, i.e. discarding what seems inapplicable in your context.

I hope this advice on career is helpful. May you discover new loves, keep learning, and to keep growing in happiness. 🙂

Updated date 6 Aug 2021